A Tale of Two MVPs

Modern software development is a dense memeplex teeming with patterns, methodologies, and practices that rapidly mutate and recombine with each other in novel, often infuriating ways. “Agile” is famously a term whose meaning is nebulous and ever-shifting, applied to any set of development processes up to and including waterfall. Another is “Minimum Viable Product,” or MVP. Originating with a specific meaning in the Lean Startup movement, MVP has since morphed into a general notion in software development of the small, focused, well-honed feature set of an initial release milestone.

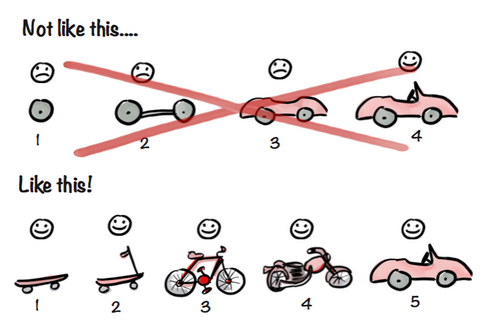

Both ideas are valuable, but problems emerge when wisdom that pertains to one kind of MVP is blindly applied forward to the new, mutated MVP. A great example is this graphic, which I’ve mentioned before and just now stumbled across in an article on software versioning:

While I do not know the exact provenance of this graphic (Update: It’s either created by Henrik Kniberg or directly derivative of his work), I can very confidently state that it originally applied not to software development, but to the original Lean Startup concept of the Minimum Viable Product. I know this because it is a great illustration of the MVP in a Lean Startup, and an absolutely horrible illustration of the MVP in software development.

The MVP in Lean Startup is Concept-First

Lean Startup isn’t a software development methodology—it’s an approach to entrepreneurship and business. The Minimum Viable Product, properly applied, isn’t a trimmed down version of a sprawling—if undocumented—business plan. Rather, it’s the quickest, cheapest, easiest-possible solution to whatever problem the company is tackling in order to make money. In the context of Lean Startup you don’t sit down, dream up “we’re going to be Twitter/Yelp/Google/Vimeo/Foursquare for Quickimarts/Bus stops/Bowling alleys/Dog parks,” excitedly plot out some expansive ecosystem/plan for world domination, and then scale that all back to an MVP. Instead, first a monetizable problem—something for which you can sell a solution—is identified, and then a quick-and-dirty fix is plotted out in the form of the MVP.

The reason the comic makes a lot of sense from this perspective is that you explicitly do not start out with aiming for the moon and then having to adjust your sights downward—there’s money sitting on the table, and you want to start snapping it up as quickly as possible using whatever tools you can. Software development is actually a worst-case scenario, from a Lean Startup perspective, so piecing together a gold-standard system from scratch is understandably discouraged.

Instead, the “skateboard” solution might take the form of something as simple as a Google Sheets/Forms, or Filemaker Pro app. What matters is that you solve the problem and that you can monetize it. The “bike” solution might be a tricked-out wordpress site with some custom programming outsourced to a contractor. In this context, it doesn’t matter one bit that each solution is discontinuous with the next, and is essentially thrown away with each new version—what matters is that money start coming in as soon as possible to validate the idea, and that the solution (as distinct from software) is iterated rapidly.

The MVP in Software Development is Software-First

You’d be hard pressed to find a professional software engineer who’ll respond “Excel spreadsheet” or “Wordpress site + 20 plugins” when asked to describe an MVP. It’s simply a different country. The core idea—do as little work as possible to get to a point where you have something to validate the solution—is retained, but the normal best practices of good code design and project management are still paramount.

As software engineers, we’re not going to half-ass a partial solution to a problem, pretend it’s a skateboard, and then throw that work away to start on the scooter iteration. Instead, an MVP is the smallest app we can write well that is still useful and useable. From there, we iterate and experiment with new features and functionality, taking into account real-world feedback and evolving demands and opportunities.

From a product perspective, we need to take a look at what we mean by minimal and by viable. Minimal, in one sense, means simply stripping things away until you get to a vital core. The tension is with viability—probably the most ambiguous of the three parts of “MVP.” Some take the position that “viable” is in relation to the market… something is “viable” if it can be sold or marketed to users. I argue that “viable” is to be taken in the same meaning as a foetus being “viable,” which is to say it is able to be carried to term. A minimum viable product, then, is the smallest set of features which can conceivably be developed into your product. An MVP should consist of an essential, enduring core of code that will form the foundation for further efforts. Anything else is simply a prototype or proof of concept.

A Concept-First Software MVP Can Be Disastrous

As erroneously applied to software, this can also be called the teleological MVP, or alternatively the function-over-form MVP. This approach emphasizes the principal value we’re delivering for our users rather than how we intend to manifest that in a final product. That value is distilled, and minified, until we have a vision of a product which is significantly less effort than what we actually intend to make. So, if we’re trying to create a sports car, as in the comic, you might interpret the value as “getting from point A to point B more efficiently than walking,” then squeeze that down until you arrive at a bike. Or a skateboard.

The chief problem with concept-first is that the MVP does not exist in a vacuum. Like any tool it has to be measured by how well it helps us achieve the intended results. If you’re developing a sports car—or the software equivalent—then an MVP is only valuable to the extent that it helps you to produce, eventually, a sports car. If you develop as your MVP the skateboard version of a sports car, where do you go from there? The only thing you can possibly do is to throw the skateboard away and start over, or become a skateboard company.

The comic illustrates this process with smiley faces, implying that with each version you have happy users and thus are on the right path. In reality, it shows four product development dead-ends amounting to—in real terms—thousands of hours and potentially millions of dollars of wasted time and effort. Take, for instance, the case of Gamevy, which produced as the MVP for their real-money gambling business a “freemium” fake-money product which—while certainly less effort and time-intensive than their ultimate goal—nearly doomed the company.

Forget The Cutesy Comic

That comic, at the top of this article? It’s about Lean Startup MVPs. It isn’t about developing software. The process it has crossed out as undesirable is actually the approach we want to take to development software—good, well-architected systems composed of ever more generalized, ever more fundamental systems. Don’t program a skateboard when you mean to program a motorcycle—you might turn out “something” sooner than you otherwise would, but it is a false savings and you’ll pay for it very, very quickly.