iOS Design Patterns: Part I

I’m working on a brand-spanking-new iPhone app, for the first time in a while, and I’m trying to take a fundamentals-first, good-design approach to development, rather than simply regurgitate the patterns I’ve used/seen in the past. Here are three “new” approaches I’m taking this time around. Each of these patterns are broadly applicable regardless of your language or platform of choice, but with iOS development, and XCode, they can take a form that, at first, might look odd to someone used to a particular style.

Clean Up View Controllers With Composition

Ever popped open a class and seen that it conforms to 10 protocols, with 20-30 mostly unrelated methods just piled on top of one another? This is a mess: it makes the class harder to read and debug, it makes individual lines of logic harder to test and refactor, it can mean an explosion of code or subclasses you don’t actually need, and it precludes sane code reuse.

By applying the single responsibility principle—and the principle of composition-over-inheritance—we can mitigate all of those problems, moving code out into individual classes for each protocol/responsibility. You’ll win gains pretty quickly when you realize, for instance, that a lot of your NSFetchedResultsController-based UITableViewDataSource code is nearly identical, and a single class can suffice for multiple view controllers.

That goes for view code, too: If you’re poking around in the view layer it’s probably a good idea to do it in a UIView subclass. The name of the game isn’t to minimize the number of classes in your project, and separating code by function appropriately is the basis of good code design. For that matter, the name of the game isn’t merely “code reuse” either—whether or not you’ll ever take two classes and use them independently isn’t the mark of whether they should just be smooshed into one giant class.

Cut Your Managed Objects Down to Size

What’s the responsibility of your NSManagedObject subclasses? To coordinate the persistance of its attributes and relationships. That’s it. Taking that data and doing various useful things with it is not part of that responsibility. Not only do all those methods for interpreting and combining the attributes in various ways not belong in that specific class, but by being there they are manifestly more difficult to test and refactor as needed. If you’re looking at a bit of code to—I don’t know—collect and format the names and expiration dates of someone’s magazine subscriptions, why should that code be dragging all of core data behind it?

At a minimum, most of those second-order functions can be split out into a decorator class or struct. A decorator is a wrapper that depends simply on being able to read the attributes of its target object, and can then do the interesting things with reading and displaying that data—without involving core data at all. How do we eliminate core data entirely? By using a protocol to reflect the properties of the NSManagedObject subclass. Testing any complex code in your decorator is now a cinch—just create a test double conforming to that protocol with the input data you need.

This is a super simple example of a decorator I use to encapsulate a Law of Demeter violation. This illustrates the form, but the usefulness pays increasing dividends as the code gets more complex. Note, also, that you needn’t have a single decorator for a given model… different situations and domains might call for differentiated or completely orthogonal decorators. In that way, decorators also provide a way to segregate interfaces appropriately.

protocol ExerciseAttributes {

var weightType: NSNumber? { get }

var movement: Movement? { get }

}

extension Exercise: ExerciseAttributes {}

struct ExerciseDecorator {

private let exercise: ExerciseAttributes?

init(_ exercise: ExerciseAttributes?) {

self.exercise = exercise

}

var name: String? {

return exercise?.movement?.name

}

}Storyboards Can Help Manage Composition

I used to have a knee-jerk reaction to storyboards. They felt like magic and as if all they did was take nice, explicit, readable code and hide it behind a somewhat byzantine UI. Then I realized what they really do: they decouple our classes from each other. The storyboard is a lot like a container. It lets us write generic, lightweight classes and combine them together in complex ways without having to hardcode all those relationships, because there’s another part of our app directing traffic for us.

After you’ve moved all your protocol and ancillary methods from your view controllers, you’ll probably end up instead with a bunch of code to initialize and configure the various objects with which the view controller is now coordinating. This is an improvement for sure, but you still end up with classes that mostly exist just to strongly couple themselves to other classes. That glue code is also so much clutter, at best. At worst it has no business being in your view controller class at all, but for a lack of anywhere else to put it. Or is that so?

Amidst the Table View, Label, and Button components in the Interface Builder object library is the simply named “Object” element. The description reads:

Provides a template for objects and controllers not directly available in Interface Builder.

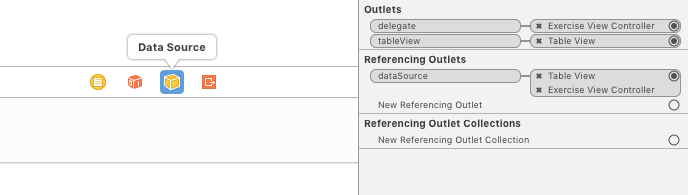

“Not directly available in Interface Builder?” Then what’s the point, if we can’t do anything with it? Ah, but we can do things with it: we can hook up outlets and actions, and configure the objects with user-defined runtime attributes. We can, simply put, eliminate large swaths of glue code by letting the storyboard instantiate our coordinating classes for us, configuring them with connections to each other and to our views, and even allow us to tweak each object on a case-by-case basis. All with barely any code cluttering up our classes.

You might have a strong intuition that a lot of that belongs in code, as part of “your app.” If so, ask yourself: if this belongs in code, does it belong in this class? Truly? Cramming bits of orphan code wherever we can just to have a place to put them is a strong code smell. Storyboards help eliminate that. Embrace them.

Huge drawback: The objects you instantiate this way have to be @objc, and as such you can’t have @IBOutlets for a protocol type that isn’t also @objc. This means you lose the ability to pass and return non-Objective-C types such as structs, enums, or tuples. This is really frustrating and a significant limitation on using the technique to clean up your view controllers more generally.